Page-1

|Page-2

|Page-3|Page-5|Page-6

|Page-7

|Page-8

|Page-9

| Page-10

| BaKhabar  Download pdf Download pdf

|

| A Glimpse into Bygone Days --- By S.G. Jilanee <sjila_104@hotmail.com>* A nostalgic account of the

numerous cultural traditions prevalent in the Indian subcontinent;

today, it sounds like a fairy tale

This is the story of the times, not very long ago, when life moved at a slow pace. There was plenty of time not only to “stand and stare,” but much more. With gold selling at Rupees 22 per tola (12 grams) and other necessities of life aplenty and cheap (pure ghee sold at less than one rupee a seer) there was cheerfulness all round.  Festivities and ceremonies were frequent. Some were quite elaborate. Chhati was observed on the sixth day of the birth of a baby. It was the occasion for naming the newborn marked with much rejoicing. Weaning of the baby at the age of “30 months” and giving it the first taste of savoury food was another occasion to enjoy. Bismillah was performed when the child was about four. This was an elaborate ceremony, Draped in the best attire, the boy or girl sat, respectively, before a maulvi, or ustani (female teacher), and repeated bimillah as recited by them. After the ceremony gifts would rain on the child and there would be a joyous feast.  Girls went through kaan chhedan (ear-piercing) at about the same time as bismillah. Their ear-lobes were pierced with a needle and they bore the pain with a grin to be able to wear ear rings. Between seven and eight years of age kids were initiated into Ramadan fasting. The first day of fasting was celebrated with as much éclat as the Bismillah. The beauty of it was that all the iftar cooking was done at home. Dolls’ weddings were other occasions for partying. Girls would do matchmaking between the male doll of one and the female doll of another among their friends. All customs and rituals of real marriages were observed; invitations, henna, barat, nikah, rukhsati, waleema and chauthee (fourth day after wedding) under the guidance of elders, only on a mini-scale. When girls reached the age of puberty, their first menstruation was an event of great joy in the family. As Bilquis Jahan Khan narrates in her autobiography, A Song of Hyderabad, her first menstruation was greeted with a “seven-gun salute from her maternal grandfather’s Arab guards.”  Weddings were the apex of all rejoicings. The bride’s home became the centre of festivities from almost a month before the event with frequent visits from relatives. Seamstresses worked on bridal dresses. (There were no readymade jodas)  About 15 days before the wedding the bride was confined to a dimly lighted room, lest the sun should burn the fairness of her skin. This was the maiyoun. During this period ubtan (fragrant herbs ground to a paste with gram flour) was rubbed regularly all over the bride’s body and especially her face.

A paste made from fresh henna leaves was applied all over the palms, fingers and nails of both hands, without any designs or patterns. This lent a lasting fragrance to the hands. After the nikah had been solemnized, reciting a laudatory poem for the groom was a hallowed tradition. How it caused a spat between Ghalib and Zauq at the wedding of Prince Jawan Bakht is history. When the bridegroom was led to the women’s section to perform the many rituals the entrance was blocked by the bride’s younger brothers. A fee was negotiated before the blockade was withdrawn. This custom was reversed when the bride arrived at her new home. Her palanquin was blocked by the groom’s younger brothers.

When the groom took off his shoes to walk on the carpet, the bride’s sisters stole his shoes, which were returned, again, after some reward. An important ritual was arsi mas-haf. The newly-weds sat side by side, with a sheet over their heads. A mirror was held up in which they saw their reflection (for the first time in cases where the bride and groom were strangers) Meanwhile, outside the guests would be entertained by professional songstresses or regaled by bhands and mirasis (traditional jokers). There was no photography. The bride did not appear before male guests. For four days until chauthee she kept her eyes shut, except before her husband and the closest relatives in the secrecy of her bedroom. Roo-Numayee was a formal ceremony on the chauthee day. The bride sat on a carpet (farsh), eyes shut. Her attendant gently lifted her chin for the guests and relatives to see her face as they filed past and offered money as salami. After chauthee the bride returned with her spouse to her own home for a brief period before she finally went back to settle in her new abode. All that is now a sweet dream! (ends)  |

Bakht

Khan: Winner of a lost battle –

Part2

… By Asma Anjum*

A much

garlanded and battle hardened veteran of Afghan wars, with huge

handlebar moustache and sprouting sideburns…. Known personally to

several of the British officers. [Part-1]

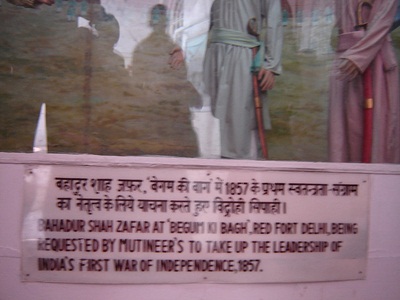

"Mutineers" or Freedom Fighters?: Museum at Red Fort continues to insult our heroes by calling them "mutineers." P.C. Joshi in his work, Inquilab 1857 makes a significant observation about this term, Wahabi. He says that, “The use of the term Wahabi is not at all correct, because the political ambitions and social views of allegedly Indian Wahabis were not based on Abdul Wahab of Najad but on the man who came before him. He was Shah Waliullah [died:1762]. That’s the reason some supporters of Islamic renaissance like, Ubaidullah Sindhi [1861-1948], Ghulam Sarvar and [Hakeem] Ajmal Khan have preferred to call themselves as Waliullahi or the followers of Shah Waliullah. But I have maintained this word due to its popular use and historical importance.” His Wahabism thus had Indian roots. Hence despising the Rohella Subedar as a Wahabi is to belittle the efforts he made for a unified fight against our former rulers. It is unfair to the man in question who is among the real heroes of the mutiny. Noted historian Irfan Habib too condemns the practice of labeling and cornering him as a Wahabi and describes Bakht Khan as, “the republican minded commander–in-chief in Delhi, who is most unfairly portrayed as a Wahabi in some modern accounts.” Wahabi or not, what is important to notice, is that he struggled for unity among the different religious sects and led the Fauj-e-Hindustani and fought for a unified and free India. Barun De admires this General of Bareilly for providing the quintessential unity that was severely lacking among the ranks of the rebels. He terms Bakht Khan a true leader and lauds his efforts at unifying different forces of the time, as worth studying.  My attempt here is to present a brief sketch of this great General as a figure who, till his last, struggled for the dream of a free and unified India where harmony among different ethnic groups was his top priority. His Origins:  Bakht Khan was of Rohilla [Afghan] stock. His grandfather Ghulam Qadir Khan came to Lucknow to make a living. His father Abdullah Khan, said to be a very handsome man, was married to an Awadh Princess. Bakht Khan was formerly a Subedar in the 8th Foot Artillery at Bareilly and had served the British for over forty years and fought bravely in Afghan wars. He had progressed quite rapidly and was appointed in a high-ranking position there. Interesting to note, is his close friendship with many British officers, under whom he had served and imbibed the art of war. Colonel George Bourcheir was educated in Persian by him, and who describes his tutor as, “very fond of English society …..[and] a most intelligent character.” But quite a few disagreed and called him, a fat guy, socially ambitious and an incompetent horseman, probably the worst insult for a soldier, in those times. His commanding officer, Captain Waddy [BHA], describes him thus, “ He is sixty years of age and is said to have served the Company for forty years; his height 5 feet 10 inches; 44 inches round the chest ; a very bad rider owing to a large stomach and thick thighs but clever and a good drill”. When the revolution began he was already in his native town of Bareilly and his fame as a fine administrator and a brave and especially able army commander had spread in the country. He had arrived in Delhi with a huge contingent of 7000 [according to another source, 14000] cavalry and hundreds of infantry and a treasure from Bareilly. Bakht Khan as an Administrator: It is indeed quite fascinating to know Bakht Khan’s efforts in trying to enforce some kind of sense and sensibility, onto the madness of loot, plunder and sheer chaos of the Delhi of 1857 uprising. He tried every trick in the book to restore law and order amid that disturbing pandemonium. Munshi Jeevan Lal, the overweight Mir Munshi [Chief Assistant] of Resident of Delhi, Sir Thomas Metcalfe [who was working as a British spy, describes how General Bakht Khan went about restoring order amidst that unprecedented anarchy spread after the arrival of the rebels, in the capital. It’s a human thing to love admiration; but when it comes from the enemy, it becomes doubly significant. Munshi Jiwan Lal in the notes to his British Masters appreciates measures taken by Bakht Khan. There were to be no taxes on salt and sugar, looting [by the just arrived rebel soldiers] had to be stopped else their plundering hands would be cut off, shopkeepers were to be given full protection and even encouraged to use weapons [if they had none, then would be duly provided from the state armoury], soldiers were to be removed from the Dilli bazaars as it created difficulties for the general public and relocated in camps outside Delhi gate, their salaries were to be restored and promises of jagirs were made to them in return of their services to the army. He further informs that the General’s men had also killed three spies working for the British [M.Baqar Ali, father of Muhammad Husain Azad, the famous Urdu writer, too, had complained in his first report that, he is followed by the spies of Bakht Khan wherever he goes.  The Metcalfe’s Munshi tells his masters that General Bakht Khan was soft spoken to his men but also remained firm that, they should not cross their line of duty even in the smallest measure. Impressive army parades were conducted by him from Delhi Gate to Ajmeri Gate. Many important petitions from various kings, Nawabs, Rajas, and officials of courts, were forwarded to the King and replies were received through the office of Governor General Bakht Khan; chief among them were, Qudratulla Khan, Risaldar of Awadh, Khan Bahdur Khan, Rao Tula Ram. A ruqqah was also addressed to the Patiala Rajah, conveying pardon of the King for his faults, many other such instances of accessing the King through the General can be found in different accounts of history. Here he was playing the role of a keen diplomat. His honest and sincere attempts at running the administrative affairs efficiently at court and his diplomacy with the men of importance are discernible from these accounts. The steps he took to restore a sense of sanity in those insane times are evidently commendable but somehow go unnoticed by his critics. Bakht Khan as a military strategist: The General was a shrewd military strategist. What he achieved at the battle field of Delhi becomes more significant considering the dire circumstances he worked in. He had little support from his own army factions and was constantly attacked and maligned by some hostile elements from within. His strategies on the battle field, his trying to sabotage the passages that took supplies to their camp, invention of rota system and his playing the mind games with the enemy, all are indeed splendid. Richard Barter gives tribute to this great man thus: “Thanks to the system organized by Bakht Khan…..We were scarcely able to stand….” He was speaking, worn out at the battle ground along with his soldiers, thanks to the new General’s machinations. Their frustration grew to the extent that some of the British soldiers seeing no sign of relief wanted to kill themselves on purpose, and some even did. Be it propelling a contingent to Alipore or setting up a new rota system intended to engage the British forces on a daily basis, and which meant leaving them no respite from the combat, General Bakht Khan always worked on new strategies to defeat his enemy. Soon after his arrival, on the ninth of July he made a massive attempt to destroy the British forces and one of his strategies was to clothe his men in British white uniforms. This took the opponents by surprise and a deep access was gained into their camp. Such regular expeditions by Bakht Khan frustrated the enemy to the extent that, they began losing all hope of capturing Delhi again. He succeeded as he knew the British tactics inside out .His long service to them had at last, paid off.  * Asma Anjum (Khan), a social reformer, is exploring the partition of India with a view to understand the largest political divide of muslims in the 21st century. She can be contacted on asmaanjum.khan@gmail.com |

|

4

Home

| About

Us | Objective

| Scholarship

| Matrimonial

| Video

Library | Projects | Quran

Resources | Lend

a hand

|